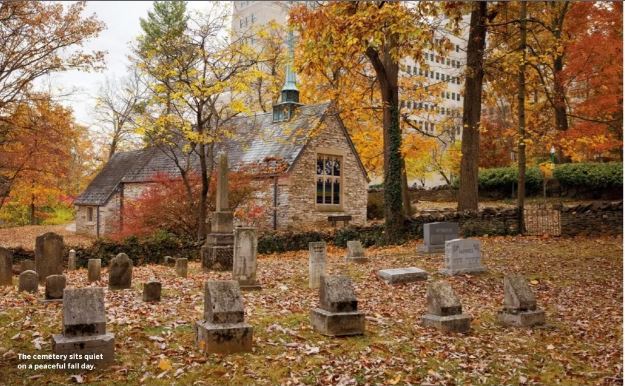

The Dunn Cemetery–Indiana University (Part Two)

NOTE:

The following article was originally published in the Fall 2023 edition of the Indiana University Alumni Magazine. Aerlex Law Group founder and President Stephen Hofer is an Indiana alumnus and thought our Aerlex audience might find it of interest, even though it’s definitely “off-topic,” at least as far as business aviation is concerned. This is the second in a four-part series. Stick with it through all four parts – we think you will ultimately be at least a little entertained and charmed by what you’ll learn about the Indiana University campus, a pioneer graveyard, Revolutionary War patriots and the founder of our firm.

By Deborah Galyan

A Curator of a Different Sort

Despite its prime location, IU cares for, but does not own the cemetery property. The Dunn family used the site as a family cemetery from the time they arrived in the 1820s, but it wasn’t until 1855 that the use of the lot was codified in a deed written by George Grundy Dunn Sr. (a son of Samuel and Elizabeth Dunn). In the deed, Dunn Sr. defined the lot size and dedicated the cemetery to his grandmother, Ellenor (Brewster) Dunn, and two great-aunts, Agnes (Brewster) Alexander and Jennet (Brewster) Irvine. It declares that only direct descendants of the three Brewster sisters can be buried on the property.

As anyone who has tried their hand at genealogy knows, proving direct descent from an ancestor isn’t always easy. Through the years, IU has sought expertise from those who know the Dunn-Brewster history well enough to determine the eligibility of individuals who petition for burial in the cemetery. Luckily, Stephen Hofer, BA’76, is one of those people.

Since 2006, Hofer has served as genealogical curator of the cemetery, voluntarily working with IU administrators who oversee the property to ensure that the family’s original intentions are honored. His considerable knowledge of family history is critical to the role. And he represents a rare convergence: He’s an IU alum and a direct descendant of not one, but two, Brewster sisters—the result of a marriage between two first cousins, when such marriages were not unusual. “Agnes and Ellenor are my fourth great-grandmothers and Jennet is my fourth great-aunt,” he explains.

In the 1970s, Hofer majored in journalism and political science and was active in student government. While still a student, a talent for reporting landed him a part-time job at Bloomington’s Daily Herald-Telephone and then a promotion, at the age of 22, to managing editor. He spent a fair share of time in Simon Skjodt Assembly Hall, watching the storied 1975– 76 Hoosiers make NCAA men’s basketball history. After graduation, he worked at the prestigious Miami Herald until moving on to law school at Northwestern University.

Today, he is a highly respected Los Angeles lawyer and the founder of Aerlex Law Group, one of the nation’s premier aviation law firms. His law career of 40-plus years has been unequivocally successful—his firm serves a roster of A-list clients, both Hollywood royalty and superstar athletes.

Separating Facts from Myths

In his student days, Hofer was aware of a familial connection to the cemetery, but not especially interested. “I was like most people. You don’t get interested in genealogy until all the people you want to ask questions of are already dead,” he says, laughing.

Having grown up hearing tales about ancestors who fought in the American Revolution, Hofer set out to learn more about his family—motivated by a desire to find records that would enable his mother to be inducted into the Daughters of the American Revolution in time for her 80th birthday. “I thought— this ought to be fairly easy,” he says, with a glint of irony. “And in fact, it took about a year. We didn’t get it done in time for mom’s 80th birthday, but we did it. Everything has to be documented, every single birth, every single death, every single marriage, and the children, going down to the next generation.”

Today, Hofer is a seasoned genealogist with formidable knowledge of his Dunn and Brewster ancestors. For some years now, he has been working on a book-length history, drawing on years of legal expertise combined with investigative reporting skills. He has identified a collection of authoritative sources to guide his research—not an easy task, particularly in pre-internet times— joined heritage societies and tracked down relatives for leads that might help a struggling researcher find a missing link.

“The thing about genealogy is, if you can back it up, it’s fact. If you can’t, it’s mythology,” he says.

Moles and Hoagy

A morning walk through the cemetery with IU’s Mitch Druckemiller and Larry Stephens, BS’73, serving as guides takes on an interesting dimension. Both view the grounds through the eyes of property managers and stewards. Druckemiller, an assistant director with IU’s Office of Insurance, Loss Control and Claims, or INLOCC, is still learning some of the unique aspects of oversight from Stephens, the retired director of INLOCC and a risk-management specialist for more than 35 years.

Clearly, both have a fondness for the historic property and its challenges. Over the course of an hour, they discuss plans to hire experts to clean and repair fragile gravestones without damaging their carvings, how to discourage moles from tunneling through the grounds, and the need to restore a few sections in the handsome limestone fence.

The lack of certainty about the number and location of graves makes it difficult to determine how many sites remain open to the family. The best estimate is less than a dozen, including a section designated for cremains. Stephens and Druckemiller have worked with the Indiana Geological Survey to create a map of the cemetery using ground-penetrating radar, a non-invasive method sometimes used to investigate historic cemeteries. They are awaiting interpretation of the results to get a clearer view of what lies beneath the ground.

NOTE: This is the Second of Four Parts.